BABEL – We interviewed Ivó Kovács and József Iszlai

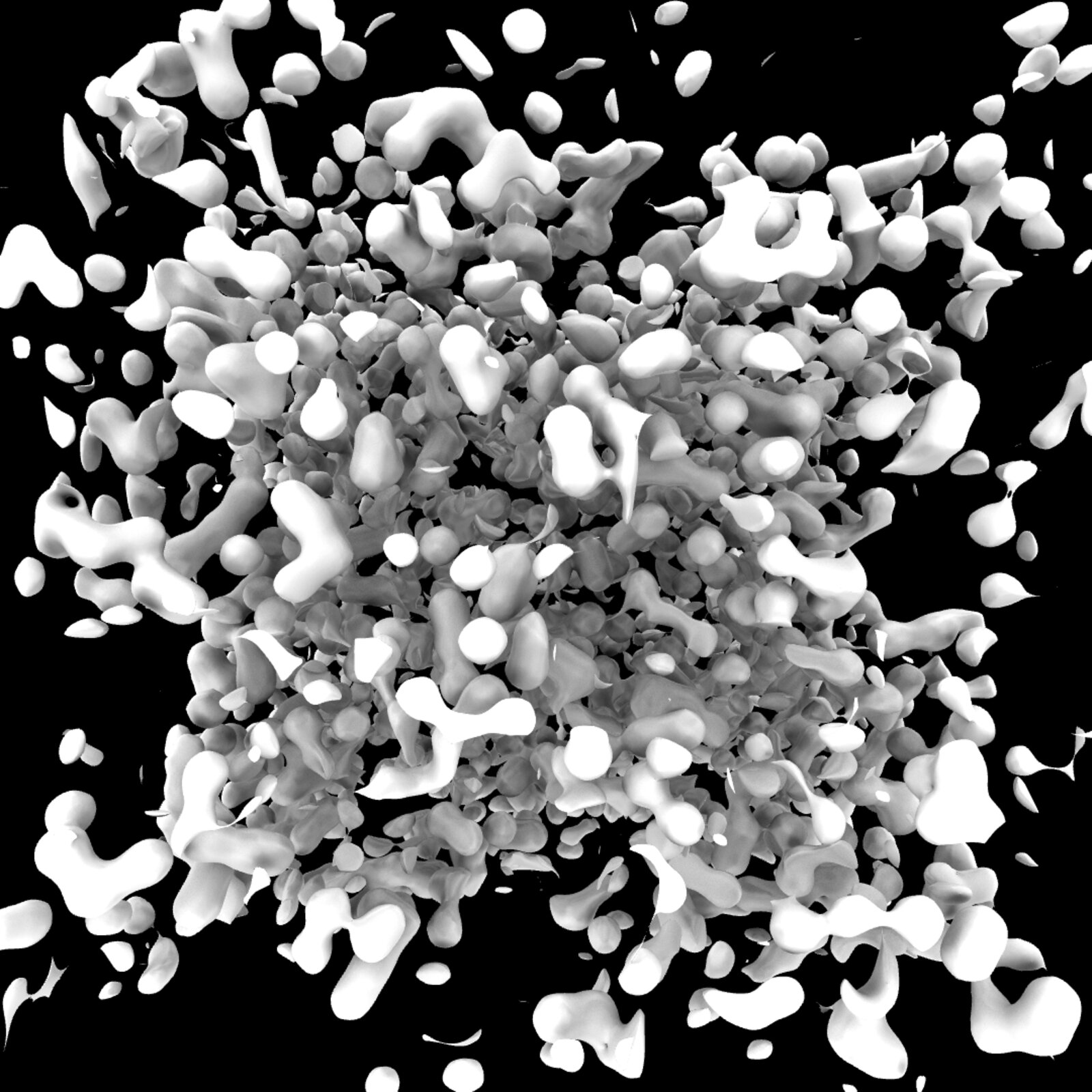

The is an audiovisual journey that explores the dynamics of a space filled with noise – an endless, changing structure that is both chaotic and secure. The creators, Ivó Kovács and József Iszlai about the creation of the concept, AI, and their reflections.

Ivó Kovács

The first question is for Ivó. How did you get started in digital art? What do you think it takes for someone to get into digital art?

Ivó Kovács (video): as a painting major at the College of Fine Arts, I painted abstract pictures that I wanted to set in motion, which led me to 3D animation, where I could build spaces that couldn't be captured on video, for example. At first, I postponed it for a year because of a school project where they were looking for a painter for three American-Hungarian feature films. Here, we went through the entire repertoire, from the creation of the frescoes to the retouching of the recordings. As autodidacts, we wanted to find out if there were any rules governing digital art as opposed to traditional art; but of course, here too, you just need to know how to paint. You can teach perspective: I taught projection mapping for a couple of years, but even today, you have to learn the software on a daily basis, so the feeling of being self-taught never goes away, and for that I am grateful.

What techniques/technologies do you use in the creation of your works?

József Iszlai (music): From a musical point of view, software is secondary to me. Technology can always offer new solutions, but a simple acoustic instrument can do that too. Personally, I expect my own technological tools to surprise me while recording music, so it's important for me to be able to try out different settings or play around with them.

Ivó Kovács: I used real-time 3D programs, into which elements generated with traditional 3D programs could also be imported. The goal was to generate everything possible when calculating the image so that the image would remain within interpretable limits and the rendering time would be shorter despite the high resolution, making the workflow less tedious.

How did the basic idea for "Homogeneous" come about? What inspired you to create this visual representation of space, symmetry, and asymmetry?

The basic idea, in the visual adaptation of Borges' short story, was (video) noise, which in its elements could contain any image, just as books contain texts in the infinite Babel library. This would have been spatial noise, which condenses, and where it condenses, it contains traces of meaning. Naturally, I thought about this in terms of a generative process, which is characterized by the fact that it can be varied to infinity and can only be stopped, not finished. This is the third version, which evolved over two and a half months from the initial noisy story. It has become quite a traditional story, but that's how it goes for the creator, if the viewer's point of view is also taken into account.

Ivó, what do you think viewers feel or think while watching the content? What experience or thought would you like them to take away from this work?

"If we break down information into its constituent parts, we lose its meaning," according to the old axiom. Borges' short story also conveys this kind of disillusionment, as if everything had been written down, but nothing at all. Or, if anything can be written down, then nothing at all. Looking at today's world, we can identify with this, just think of today's AI chat programs. While these AI programs can only create seemingly new texts or images from the information already programmed into them, the human mind secretly hopes that there is still something unknown waiting to be discovered. This seems like an avant-garde utopia in our dystopian reality—I wanted to express this optimism in my work.

At the beginning of the video—as a quasi-prelude scene—we see a brief "evolution," with noise filling the space, expanding, becoming more complex, structured, and developed, until at the end of the scene, playing with physical space, the three-dimensional space — this is the Hexagon space, as a symbol of rationality, and its attributes are the red, green, and blue lines representing the x, y, and z axes — a Cartesian space. It breaks apart, tears apart, like a veil over the sea of autumn leaves. The immersive genre is a live genre; if you are here, you see it, it has an effect. It cannot be explained or watched on film; it is similar to theater: it is about the here and now, so it is okay if it reflects on today.

When I watch it on video, symmetry is the avoidance of alignment, not alignment. What is here is also there, in space, in every direction. If I approach it critically, is it the task of aesthetics to align something, or in other words: can empty spectacle entertain? But it also fits with Borges' idea that the library is infinite in every direction. I could also say that symmetry is beyond rationality, beyond the breakdown of meaning, beyond words, the transcendent, or, if I am pessimistic, before words, the tribal, the primitive. Even if the world based on rationality that made it possible for us to think about such things is disintegrating before our very eyes, at the end of the video, the image burns out in white light so that the viewers can see each other.

It is a cliché, but it is true that the world has always been a cold, unfriendly place, and the task is to humanize it.